By John G. Riley, a Distinguished Professor of Economics at UCLA

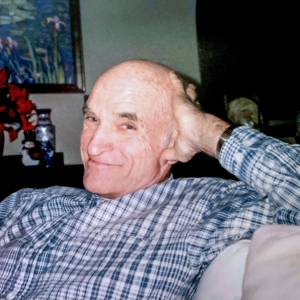

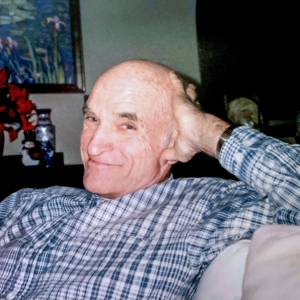

The UCLA Department of Economics is saddened to announce the passing of Professor Emeritus John J. McCall (February 28, 1933—September 24, 2018), he was 85 years old. John received his BA from University of Notre Dame and his MBA and in 1959 his PhD from the University of Chicago. He then worked full-time at the Rand Corporation until the mid-1960s and continued at Rand as a consultant for the remainder of his career. He worked briefly at University of Chicago and UC Irvine before being appointed a professor of economics at UCLA in 1970. He authored or edited several books and wrote numerous academic articles. In 1997, he was elected a Fellow of the Econometric Society. After retiring from UCLA in the late 1990s, he moved from Los Angeles to Ojai, California where he resided for the rest of his life. He is survived by his wife of 62 years, Kathy, two sons, Sean and Brian, two grandchildren, Megan and Conor, and one great-grandchild, Giovanni.

As a doctoral student, John became interested in the work of George Stigler and Jacob Marschak (who eventually become a colleague at UCLA). George and Jasha were emphasizing the importance of studying costly information transmission in a market economy. As a post-doctoral student, John wrote “The Economics of Information and optimal stopping rules,” The Journal of Business (1965). This was the first paper to provide a formal analysis of optimal stopping problems.

With imperfect information, a decision maker must decide whether to choose immediately from a set of feasible actions, conditional upon the current information, or wait and seek additional information. John fully characterized the solution to this problem, showing that the optimal strategy was a simple cut-off rule. For a broad class of problems, it is optimal to take action when some function of the additional data received exceeds a threshold.

John’s mega hit was his Quarterly Journal of Economics paper “Economics of information and job search.” In this paper he indicates that he was further influenced by Armen Alchian and William (Bill) Allen who would also become his colleagues at UCLA. An unemployed resource was traditionally viewed as an unproductive resource. But, from a search perspective, an unemployed resource is a potentially productive resource, since the owner is using the “down time” to seek alternative and potentially more valuable uses for the resource.

In the paper John analyzes the search decision of a laid-off worker. Given the worker’s beliefs about the distribution of wages in the market-place (which may be updated as the search process continues), the unemployed worker receives a stochastic sequence of wage offers. In the simplest version of the model the stopping rule has a very simple (and now well-known) form. Continue searching until the expected difference between the next offer and the current offer is equal to the expected cost of the search. The paper also showed how the simple model could be generalized to take into account the expected duration of the new job and also how to take into account learning about the distribution of wage offers.

These two papers are the foundation stones for what is now a huge search literature.

When I arrived at UCLA in 1973, John (and fellow MIT Beaver, Michael Intriligator) were the only senior colleagues whose research papers analyzed economic phenomena using more than basic calculus. John took an immediate interest in my work and remained very supportive throughout those early years. It was not always easy as some of the “University of Chicago, LA” crowd had dreams of building a department entirely on ideas emerging from the mother school. But the Chicago influence on John was deep and broad. He was fundamentally an intellectual with a very open and curious mind.

In the quarter century that we were on the faculty together, we became good friends. And even after that, we socialized in Ojai and in Pacific Palisades. Along the way we got to know and enjoy his two sons, Sean and Brian. Last but not least, John used his knowledge of optimal stopping rules wisely and married a wonderful and talented wife, Kathy. I talked to her a few days ago and she does not seem to have changed at all. She is still very energetic and fit and full of enthusiasm.

While living in Pacific Palisades (quite near our home), Kathy developed considerable skills as a modern landscape painter and sold many paintings. We have had one of those paintings on our wall for almost thirty years. I often think of her when I look up and see her painting of a Southern California evening sky. But now when I do so, I will also remember John. He was a gentle, good-hearted colleague and friend.

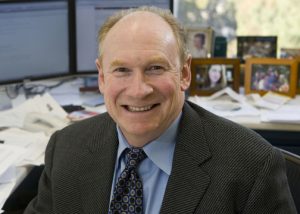

nally appeared in the August 24, 2018 print edition of the Wall Street Journal By Edward C. Presscott and Lee E. Ohanian. Lee E. Ohanian is a Professor of Economics, and Director of the Ettinger Family Program in Macroeconomic Research at UCLA.

nally appeared in the August 24, 2018 print edition of the Wall Street Journal By Edward C. Presscott and Lee E. Ohanian. Lee E. Ohanian is a Professor of Economics, and Director of the Ettinger Family Program in Macroeconomic Research at UCLA. Adriana Lleras-Muney, Professor of Economics at UCLA, was recently elected to the Nominating Committee of the Population Association of America (PAA).

Adriana Lleras-Muney, Professor of Economics at UCLA, was recently elected to the Nominating Committee of the Population Association of America (PAA). The UCLA Department of Economics is pleased to announce the appointment of David Baqaee as Assistant Professor. David received his Ph.D. from Harvard and worked previously at the London School of Economics. He works on aggregation in disaggregated macroeconomic models, with an emphasis on the role production networks play in business cycles, growth, and international trade. David’s research interests include macroeconomics, network economics, IO, and applied economic theory.

The UCLA Department of Economics is pleased to announce the appointment of David Baqaee as Assistant Professor. David received his Ph.D. from Harvard and worked previously at the London School of Economics. He works on aggregation in disaggregated macroeconomic models, with an emphasis on the role production networks play in business cycles, growth, and international trade. David’s research interests include macroeconomics, network economics, IO, and applied economic theory.